December 15, 2016 – KERR MARKET SUMMARY – Volume 6, Number 24

The world’s most notable currency has been flexing its muscles as of late. Since election night the US dollar has surged – the prospect of greater fiscal stimulus under a Trump administration fuelling expectations of stronger economic growth and tighter monetary policy. It is a surge that Wall Street has welcomed with open arms as emblematic for an economy poised to reach new heights. Yet for the rest of the globe the mighty greenback has triggered financial jitters. Some pundits suggest that further appreciation would pose a significant threat to global growth. Such is the ubiquitous role of the dollar in our world economy – when it rises, the risk-taking abilities of banks and investors are necessarily impaired. Nevertheless, our third-party research team at Capital Economics does not believe the dollar’s musculature will enfeeble the rest of the globe.

Firstly, Capital Economics forecasts a 5% growth rate in trade-weighted terms for the greenback over the next two years. We should not consider this sizeable, especially when compared to its appreciation since mid-2014 (see Chart). This brings us to our first point – substantial USD ascension and thus its associated risks are likely already behind us.

What’s more, sizeable greenback growth is only feasible if the American economy remains robust, and this benefits the rest of the world. A financially healthy United States is typically a boon for global business sentiment. It would likely benefit commodity prices as well, signifying a lift in US economic activity, most notably in commodity-intensive infrastructure spending.

What’s more, sizeable greenback growth is only feasible if the American economy remains robust, and this benefits the rest of the world. A financially healthy United States is typically a boon for global business sentiment. It would likely benefit commodity prices as well, signifying a lift in US economic activity, most notably in commodity-intensive infrastructure spending.

Arguably the main risk, according to Capital Economics, lies in the mighty greenback further emboldening President-elect Trump towards protectionism. At least history would concur. Ronald Reagan’s first presidential term also saw the dollar surge amidst a backdrop of broadening fiscal stimulus. In fact, the currency’s appreciation drove the US current account deficit above 3% of GDP in 1986. This triggered then-President Reagan to sanction “voluntary” restraints on auto exports from Japan to the US. It also introduced the Plaza Accord, an agreement between the US, UK, France, West Germany and Japan to depreciate the USD in relation to the Yen and Deutsche Mark via currency market intervention. While these efforts did not end up proving disastrous, we cannot ignore the possibility of Trump succumbing to his protectionist instincts and enacting import tariffs on China and Mexico.

A mighty greenback creates risk within the United States as well. Continued trade deficit widening is likely, as unduly currency strength reduces export competitiveness and draws imports in. While consumers disdain domestic dollar weakness as cross-border shopping and international travel become more costly, it can actually generate greater economic benefit. A rising trade deficit during the Reagan era provoked protectionism. Though a Plaza Accord revival appears implausible, especially amidst a backdrop of low inflation in Japan and Europe, President-elect Trump will start his first day in office with a trade deficit that is already large and politicised, not least of all by the man himself. This improves the odds of Trump succumbing to his protectionist instincts and enacting the tariffs he threatened during campaign season in an attempt to balance trade.

Naturally, it all depends on where the dollar goes from here. Protectionist pressures could very well be dissolved by coordinated international efforts should the strength persist. Yesterday the US Federal Reserve announced a 0.25% interest rate hike. Meanwhile, Donald Trump vows to boost US economic growth to 4% (a level not seen since 2000) and unemployment is at its lowest rate since before the global financial crisis. America arguably does not need a grand stimulus plan, and the Fed may not be an ally for Trump if the economy shows signs of overheating. As the era of Trumponomics dawns, the verdict awaits.

NEWS FOR THE FIRST HALF OF NOVEMBER 2016

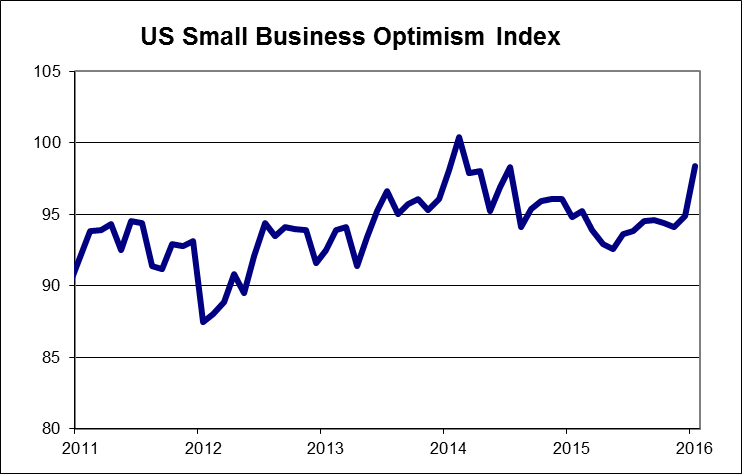

The NFIB Small Business Confidence Index for November rose by 3.5 points to 98.4. Eight out of the ten components rose, with expectations for the economy and higher sales forecasts leading the gains.

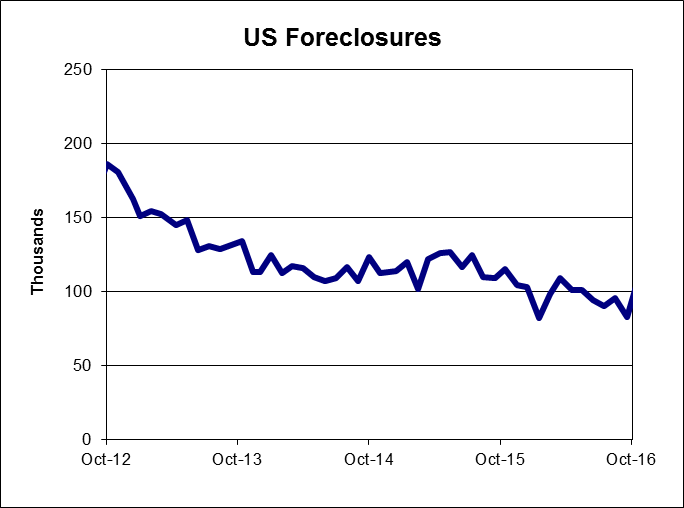

Realty Trac reported that home flipping, defined as the arm’s-length sale of the same home twice in a 12 month period declined in the third quarter after reaching a six-year high the previous quarter. The average profit on the purchase and resale was US$60,800.

US retail sales inched up by 0.1% in November, below expectations for a 0.3% rise. The October number was revised downward from 0.8% to 0.6%. Sales of vehicles and parts declined by 0.5% in November.

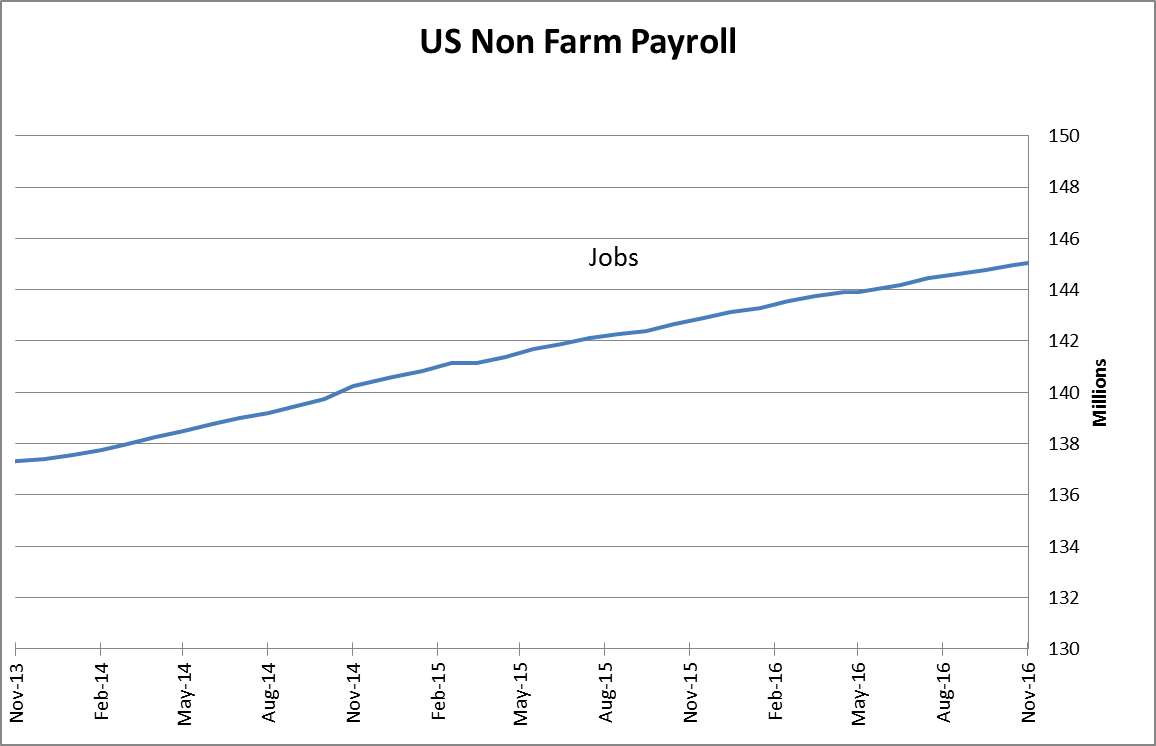

US non-farm payrolls rose by 178,000 in November, just shy of expectations of 180,000. The unemployment rate dropped to 4.6% from 4.9%, as people exited the labour force for the second consecutive month.

OTHER ECONOMIC NEWS

The ISM non-manufacturing index for November rose to 57.2 from 54.8 in October. Business activity and employment both posted strong gains. The US trade deficit for October widened to US$42.6 billion from US$36.2 billion in September. Exports fell by 2.5%, while imports rose by 1.5%.

CANADIAN ECONOMIC NEWS

Canadian employment grew by 10,700 jobs in November, with the unemployment rate dipping to 6.8% from 7.0%. However, as in October, the gains were all in part-time employment as 19.400 part-time jobs were added while 8,700 full-time jobs were lost. Canada’s trade deficit for October narrowed to C$1.1 billion from a record C$4.4 billion in September. Imports declined by 6.4%, due to a one-time import of equipment for an offshore oil project in September, while exports rose by 0.5%. Canadian housing starts declined in November to a seasonally adjusted annual rate of 184,000 units from 192,000 in October. The Teranet/National Bank home price index rose by 0.2% in November. Home prices in the markets surveyed were 11.9% higher compared to the same time a year ago.