As the recent turmoil in emerging markets continues to ignite investor fear, some experts contend that we are entering a “third leg” of the global financial crisis – the first being 2008’s U.S. sub-prime mortgage meltdown and the second the Eurozone’s near-collapse in 2011-2012. At first glance, the fears seem justified. Russia and Brazil are in technical recessions. Turkey also appears to be a flashpoint. China’s volatile stock market and weak currency are agitating global markets – the country’s meteoric rise having come to a screeching halt and leaving excessive debt in its wake. IMF Managing Director Christine Lagarde recently cautioned that EMs are “now being confronted with a new reality”. Nevertheless, a financial crisis in the emerging world may be less imminent than headlines suggest.

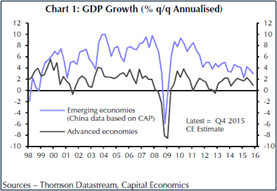

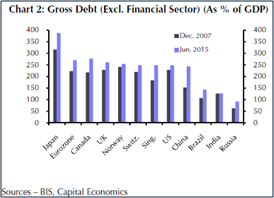

Firstly, the main issue connecting all three “legs” in this narrative is an unsustainably high level of debt. Indeed, loosened monetary policy to counter recession in the developed world may have contributed to the explosion of credit growth in the emerging world. EMs relying on commodity exports have also been plagued with price collapses, while those with sizeable foreign currency debt face further financing problems caused by a strong USD. While these risks should not be dismissed, it must also be noted that most EM growth began slowing down in 2011, therefore recent weakness is not a new development. Nor has it prevented growth in advanced economies over the last few years. What’s more, in Q4 2015 EM growth was still noticeably ahead of its developed-market peers (see Chart 1).

Moreover, there is solace in the fact that EMs are better equipped to handle external shocks than they once were, as most new debt is now denominated in local currency rather than foreign – rendering them less vulnerable to capital outflows and currency slumps. FX reserve levels have also become considerably more robust.

So are EMs in sounder shape than they appear? As it turns out, what is happening in the emerging world is not a financial crisis but a growth crisis. Concerns over the impact of a Fed tightening have triggered a stampede of capital out of EMs. In Q4 2015 outflows reached a record $270 billion – greater than the exodus during the 2008 meltdown. The IMF predicts a 4.3% EM growth rate for 2016. In 2006 that rate was 8.2% – bad news for a global economy on the hunt for new growth sources, and more importantly for the over 1 billion people still trapped below the poverty line. Could a growth crisis in one country infiltrate the rest of the EMs, as evidenced in the late 1990s? There is always that possibility. While slowing growth in the emerging world may not provide the next great global crisis, it is still one of the world’s more notable dilemmas.