June 15, 2016 – KERR MARKET SUMMARY – Volume 5, Number 12

If assessed solely based on noise levels, it seems as though “helicopter money” could be landing on our front lawns sometime soon. Also referred to as “helicopter drops” and “the citizen’s dividend”, helicopter money is a concept first proposed in 1969 by American economist Milton Friedman, who suggested that releasing money out of helicopters for citizens and businesses to collect was a sure way to revitalize the economy in deflationary periods. Today, the idea has evolved into a hypothetical monetary policy tool where the central bank would print sums of money and distribute it unilaterally to the private sector in order to stimulate demand and, eventually, nominal GDP.

If assessed solely based on noise levels, it seems as though “helicopter money” could be landing on our front lawns sometime soon. Also referred to as “helicopter drops” and “the citizen’s dividend”, helicopter money is a concept first proposed in 1969 by American economist Milton Friedman, who suggested that releasing money out of helicopters for citizens and businesses to collect was a sure way to revitalize the economy in deflationary periods. Today, the idea has evolved into a hypothetical monetary policy tool where the central bank would print sums of money and distribute it unilaterally to the private sector in order to stimulate demand and, eventually, nominal GDP.

The basic principle behind helicopter money is that if the central bank’s goal is to raise inflation and output in an economy that is running substantially below potential, a helpful tool could be to simply increase the monetarybase and deliver direct cash transfers to everyone. The approach would be a permanent one-off expansion in money supply that would enable consumers and businesses to spend more freely, which in turn would broaden economic activity, and ultimately inflation levels, back up to the central bank’s target. This would not be considered quantitative easing as the central bank would not gain any assets, and it differs from fiscal easing as it would be enacted by the central bank without increasing the government’s debt burden.

While first mentioned in 1969, since 2008 a rekindling of economists advocating helicopter money has been sparked. Their proposals reveal a disenchanted belief that conventional policies, including quantitative easing, are either unsuccessful or rendering adverse effects on financial stability along with the distribution of income and wealth. In 2013, Adair Turner, former chairman of the U.K.’s Financial Services Authority, argued that deficit monetisation was the quickest way to recuperate from financial crisis. Other experts also support its use in the Eurozone, maintaining that an interest-free cash distribution to the private sector would increase consumption and investment enough to fight E.U. stagnation.

So will helicopter money be falling out of the sky sometime soon? Well, in practical terms, there have been various proposals for injecting HM into the economy – some entailing fiscal policy measures such as government bonds or tax rebates, others involving a two-pronged process where the government issues debt and the central bank purchases it in order to finance HM operations. Empirical studies have indeed revealed that macroeconomic relief of this nature has aided certain countries, from a demand management perspective. Proponents highlight its main benefit – that unlike debt financing, helicopter money does not crowd out private investment by raising interest rates for borrowers. Supporters also underline that greater public spending guarantees higher aggregate demand, while supplementing the private sector’s income would enhance wealth more directly than a rise in asset prices via quantitative easing.

Helicopter money is also criticized, however. Some economists argue that it would weaken central bank (or public sector) balance sheets, destabilize a country’s currency, reduce the population’s incentive to work, or go so far as trigger runaway inflation, a phenomenon that is tremendously difficult to reduce and/or control. Others are not even convinced that individuals would spend enough of their newfound wealth – that they would put it away for saving instead.

Yet the fact remains that roughly eight years after the onset of the global financial crisis, growth and inflation in most of the developed world remains tepid despite central bank action. With unconventional approaches such as negative interest rates ostensibly falling short, out-of-the-box measures like helicopter money might be worth a whirl.

Image Source: http://thecrux.com/helicopter-money-drops-on-europe-but-not-for-normal-folks/

NEWS FOR THE FIRST HALF OF JUNE 2016

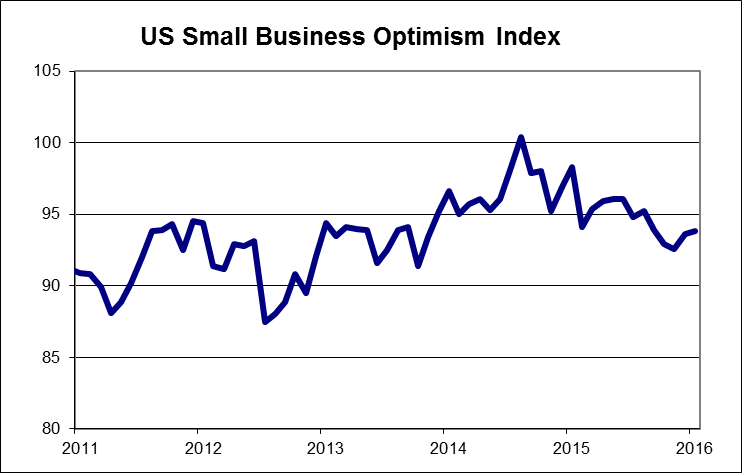

The NFIB Small Business Confidence Index for May rose to 93.8 from 93.6 in April. Expectations for the economy posted the strongest gain.

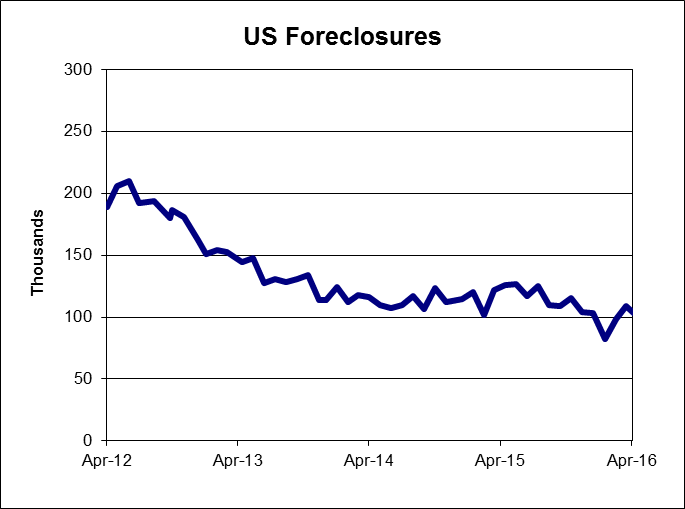

The latest Realty Trac foreclosure report showed foreclosure filings were reported on 100,932 properties in April, down 7% from the previous month, and down 20% from a year ago, the ninth consecutive year-over-year decrease.

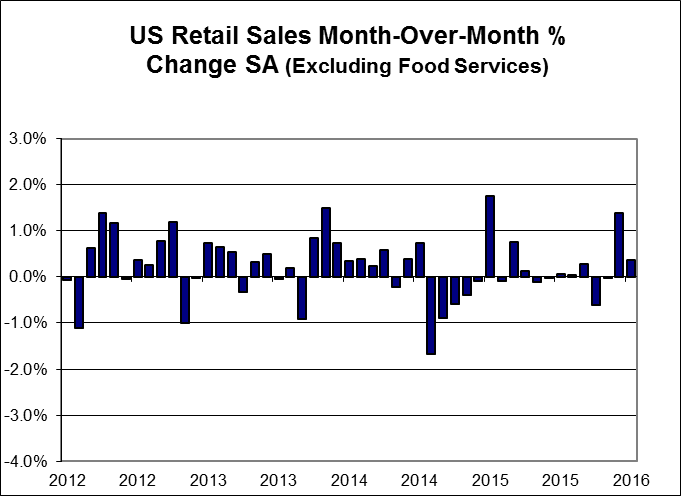

US retail sales rose by a stronger than expected 0.5% in May following a strong month of April. Auto sales helped boost the overall number, though sales ex autos were also strong, rising by 0.4%.

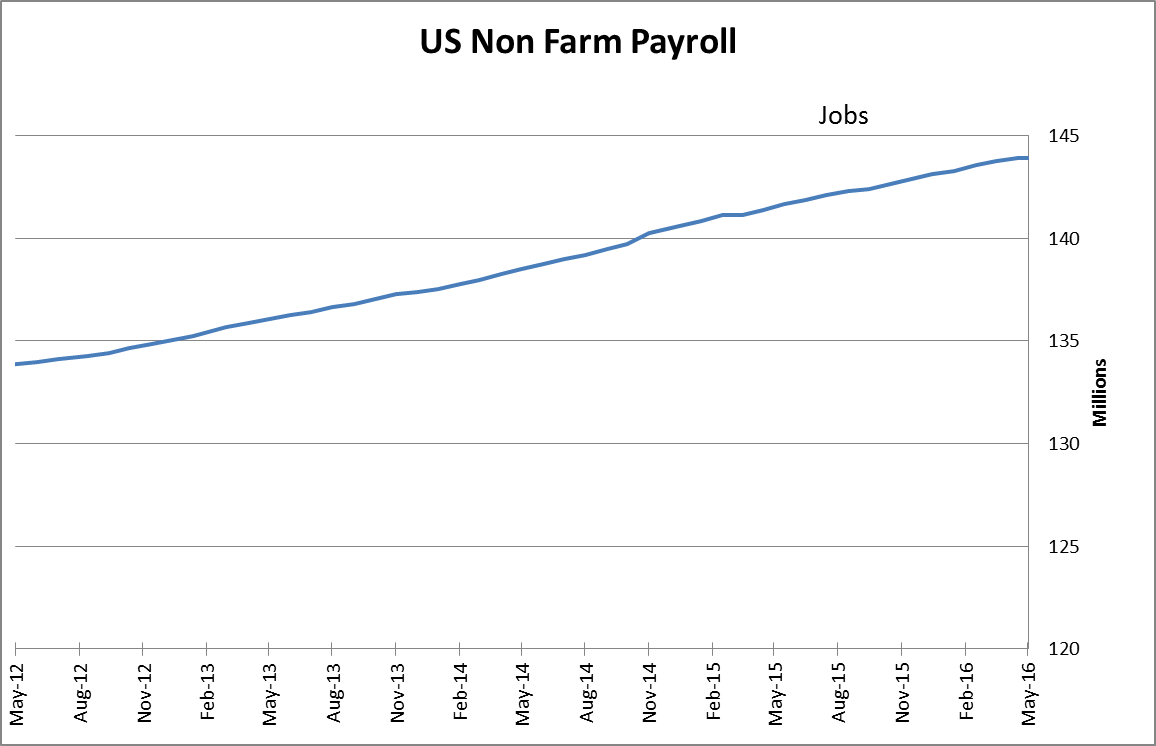

US non-farm payrolls disappointed, rising by 38,000 in May, with the March and April numbers being revised downwards. The unemployment rate dropped to 4.7% due to a reduction of 458,000 in the labour force.

OTHER ECONOMIC NEWS

The ISM non-manufacturing index for May declined to 52.9 from 55.7 in April. It is the lowest reading since February 2014 as business activity and new orders growth slowed and employment fell. The US trade deficit for April widened to US$37.4 billion from a revised US$35.5 billion the previous month. Exports rose by 1.5%, while imports were up by 2.1%.

CANADIAN ECONOMIC NEWS

Canadian employment rose by a modest 13,800 in May, as a drop in the labour force caused the unemployment rate to fall to 6.9% from 7.1% in April. Canada’s trade deficit for April narrowed to C$2.9 billion from a revised record C$3.2 billion in March. Exports rose by 1.5%, while imports were up by 0.9%. Canadian housing starts declined marginally in May to a seasonally adjusted annual rate of 189,000 units from 191,000 units in April. The Teranet/National Bank home price index rose by 1.8% in May. Home prices in the markets surveyed were 9.0% higher compared to the same time a year ago.

Sources: US Bureau of Labor Department, US Department of Commerce, RealtyTrac, US National Federation of Independent Business, and Statistics Canada, Teranet/National Bank of Canada.